Cite this Essay

MLA:

Parel, Vaibhav Iype. “Arundhati Roy.” Indian Writing In English Online, 03 July 2023, https://indianwritinginenglish.uohyd.ac.in/arundhati-roy-vaibhav-iype-parel/ .

Chicago:

Parel, Vaibhav Iype. “Arundhati Roy.” Indian Writing In English Online. July 3, 2023. https://indianwritinginenglish.uohyd.ac.in/arundhati-roy-vaibhav-iype-parel/ .

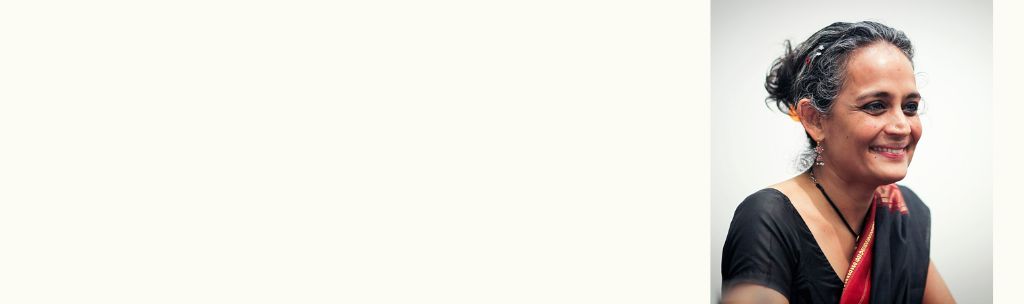

Arundhati Roy was born in Shillong in 1961. After completing her schooling from Ooty, Tamil Nadu, she left home at sixteen, to study architecture at the School of Planning and Architecture in Delhi. Interested in the alchemy of words, she never pursued a career in architecture, but urban planning and architecture left an indelible imprint in the ways she designed and visualised her future work.

She started her career as an award-winning writer of screenplays. She wrote her first screenplay for In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones (1989) in which she also acted. This was a movie that discussed her experiences as an architecture student. It won her the National Film Award for Best Screenplay in 1989. Later, she wrote for Electric Moon (1992). Both these films were directed by Pradip Krishen. Roy has also written for television serials such as The Banyan Tree (twenty-six episodes), and crafted the screenplay for the documentary DAM/AGE: A Film with Arundhati Roy (2002).

Other than the Booker Prize in 1997, Roy won the Sydney Peace Prize and the Orwell Award in 2004, the Norman Mailer Prize in 2011, the St. Louis Award in 2022, and most recently, the 45th European Essay Prize for the French translation of her compilation of essays titled Azadi. This global recognition is, however, unable to blunt the edge of controversy, anger, and hate that her writing often evokes. In fact, global recognition goes hand-in-hand with the controversy and hate that her writings arouse. Her criticism of the state is misunderstood as criticism of the nation itself. This easy and politically lazy conflation – of the state with the nation – makes her an ‘enemy’ of the nation.

Roy declined the Sahitya Akademi Award for The Algebra of Infinite Justice in 2005, stating that she could not accept an award from a government whose policies on big dams, nuclear weapons, increasing militarisation, and economic liberalism she was deeply critical of in the book for which she was being awarded the prize.[1] In 2015, she returned the 1989 National Award (for the best screenplay) in solidarity with other writers/artists to protest the rising religious intolerance in the country, as was evident by incidents of mob-lynching and the killing of rationalists. She wrote in The Indian Express, “If we do not have the right to speak freely, we will turn into a society that suffers from intellectual malnutrition, a nation of fools.”[2]

Fiction

In 1992, Roy started working on the draft of what would become her first novel, The God of Small Things (TGOST, 1997). It won her an advance of £500,000, and catapulted her to fame on the international literary stage when it won her the Booker Prize in 1997. Exquisitely written, the novel shows time to be a malleable construct. Memory, passion, and history are delicately interwoven into a rich tapestry where the past and the present inform each other, while also intermeshing in ways that obscure their separateness. This is achieved by a tightly controlled narrative that allows ‘History’ and ‘history’ to intertwine. The narrative is structured around Sophie’s death; her arrival, accidental death, and its aftermath all carefully create pathways for time, the history of small things/people/events, and their memories to coalesce around intimately explored questions of childhood, poverty, exploitation, and nature.

A fiercely feminist text, TGOST, signposts the violence that is meted out by abusive husbands and alcoholic fathers, while highlighting Ammu’s inability to possess legal rights to the property as a daughter, since she had no “Locusts Stand I” (57). As Roy calls it, TGOST “is about a family with a broken heart in its midst” (Azadi, 88). Whether it be the passionate inter-caste coupling of Velutha and Ammu, the incestuous love between Estha and Rahel, or the inter-national coming together of Chacko and Margaret, the novel speaks of love in all its shades. which, however, become threatening when their effervescence spills over the boundaries dictated by the “Love Laws. That lay down who should be loved. And how. And how much” (328). The ways in which desires spill over, and the inability of the “Love Laws” to circumscribe, contain, and define the contours of desire becomes the central strand around which much of the novel revolves. The open, free, and deliberate social transgressions that we witness in the novel challenge the social status-quo in ways that remain deeply unsettling. In fact, the last chapter of the book offended purists in Kerala enough for them to bring charges of obscenity against Roy in a court. The case took a decade to be dismissed.

Roy’s deftly woven critique of Marxism impels the narrative into directions that force upon us the recognition of the nature of politics in the Kerala of the 1960s. Her criticism is particularly sharp when she equates the Inspector and Comrade with “mechanics who serviced different parts of the same machine” (262). The novel’s audacious representation and critique of institutional complicity between the state and Marxism, while remaining deeply casteist – as evidenced by Comrade Pillai’s wife who does not allow the entry of the Paravan’s into the house – is a vector of sustained narrative tension, and attracted a sharp rebuke from the Communist Party.

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness (MUH, 2017), published twenty years later, is a dense work that mirrors the social and political changes in India in the twenty years that divide the two novels. Roy clearly wanted to do something different from her previous novel. MUH exemplifies the political as personal: whether it be the Hijras in Khwabgah, or the motley cast of residents in Jannat Guest House, Roy embraces liminality as an affective position through which to view the world. Political events like the Emergency, the Godhra riots, the insurgency and counter-offensives of the Indian Army in Kashmir, the 26/11 Mumbai attack, and the Naxalite movement feature in the novel not as distant political events that frame a background, but as personal events that have real consequences like births, deaths, and executions. The suffering and joy of the characters is narrativised through the personal, and the personal is always and unconditionally the political.

For Roy, MUH is:

a conversation between two graveyards. One is a graveyard where a hijra, Anjum – raised as a boy by a Muslim family in the walled city of Delhi – makes her home and gradually builds a guest house … where a range of people come to seek shelter. The other is the ethereally beautiful valley of Kashmir which … has become, literally, almost a graveyard itself (Azadi, 152-53).

As the city becomes a character in the novel, the poorest people and the most neglected socio-political concerns shine from the margins in an idiom that renders them unforgettable. Roy repeatedly makes visible the yawning gulf between the rich and the poor. Her fiction becomes most visceral when it mimics the cold and dispassionate indifference of the burgeoning middle-class to burning issues, questions, and concerns that lie at their doorsteps, that they are surrounded by, but are effectively blind(ed) to. Her anger, as it excoriates all shades of politicians for their apathy, raises pertinent questions about the functioning of our democracy, especially with the turn in the political fortunes of the Hindu right. The challenge that Tilo faces, “to un-know certain things” (262), resonates for the reader as well. Roy’s fiction becomes a document of our times even as she narrativises the story of many official documents like affidavits and memorandums for the reader.

Non-fiction

Compelled by a need to communicate, she follows different rhythms when writing fiction and non-fiction, by her own admission.[3] Writing fiction is a labour of joy, where she sets herself a challenging task: to close the gap between language and thought. The issues that inspire her non-fiction, however, evoke a more immediate response that is characterised by its urgency. She finds herself agitated, angry, and even sleepless. Roy’s first essay came soon after she won the Booker Prize. “The End of Imagination” (1998) was written as a response to India’s nuclear tests in May 1998 that were closely followed by Pakistan’s nuclear tests. Over the years, her writing has generated heated debates over questions of authenticity and expertise. One crucial example is her essay, “The Doctor and the Saint” that introduces B R Ambedkar’s seminal text, Annihilation of Caste (1936) that was published in a new critical edition of Ambedkar’s text by Navayana in 2014.

Roy was attacked for this essay by Gandhians and Dalits. On the one hand, scholars like Rajmohan Gandhi thought that hers was an unfair and biased representation of Gandhi.[4] On the other hand, Dalit scholars and activists claimed that since she was neither a Dalit nor a scholar on Ambedkar, her essay was a disservice to the Dalit cause based on inauthenticity (of her position) and lack of expertise (as a scholar). The debate, as it swirled on various media forums, took various forms – reviews, opinion pieces, open letters, and Roy’s replies to many of her accusers.[5] Surveying both sides of the debate, Filippo Menozzi argued in 2016:

In the case of Arundhati Roy’s debate with Dalit Camera, the witness is the one who is able to place oneself in the position of those who are oppressed, even if they have not lost their language, because they are living and they are able to speak. Assuming a Dalit standpoint is an epistemological act that does not aim at appropriating Dalit experience, but at becoming able to listen to Dalit perspectives by identifying with them; it is the precondition to challenging caste-blindness (“Beyond the Rhetoric,” 75; italics in original)

For Roy, then, it is her vocation as a writer – above all else – that allows her the freedom to intervene in political questions. In her essay, “The Language of Literature,” she explains how the struggle to communicate her political convictions to the widest audience possible impels her to find an idiom that is best suited to the task. She speaks of the form, language, narrative, and structure that she envisaged for non-fiction. She asks, “Was it possible to turn these topics into literature? Literature for everybody – including for people who couldn’t read and write, but who had taught me how to think, and could be read to?” (Azadi, 87). Describing these twenty years of writing non-fiction, she says, “I knew it would be unapologetically complicated, unapologetically political, and unapologetically intimate” (Azadi, 88). Her writing has remained, as she says, complicated, political, and intimate. The topics that have engaged her have ranged widely from the politics of the nation and the world, ecology, environment, dams, caste, the Naxals, to Kashmir, among others.

She wrestles with form and structure to allow an apparently seamless overlap between fiction and non-fiction. She gestures towards non-fiction being a universalised form of literature that is more open, democratic, and accessible, but one that is always inherently political. This overlap between what are considered distinct genres, is most evident in MUH. For Roy, “it would be a novel, but the story-universe would refuse all forms of domestication and conventions about what a novel could be and could not be. It would be like a great city in my part of the world in which the reader arrives as a new immigrant” (Azadi, 88). The topical political metaphor of the immigrant itself should alert us to the ways in which fiction and non-fiction intertwine in her writing.

Coming to fiction after having worked on screenplays, she wanted her novels to allow the multiple and playful interaction of image and metaphor in the mind of the reader. TGOST as Roy puts it, is a book “constructed around people … all grappling, dancing, and rejoicing in language” (23). It was after TGOST that she felt that she found “a language that tasted like mine … a language in which I could write the way I think” (23).

The opening essay of her collection, Azadi, is titled, “In What Language Does Rain Fall over Tormented Cities?” which is a line from a poem by Pablo Neruda. Here she explores questions of languages, translation, thought, and expression. The unsettled, uneasy, and constantly shifting relation between English, Englishes and other languages defines her fiction and non-fiction. While English has become the language of aspiration, inclusion and exclusion in India, and her novels are in English, the stories emerge “out of an ocean of languages, in which a teeming ecosystem of living creatures … swim around” (14). This multiplicity of languages/idioms, in turn, internally transforms English: “English has been widened and deepened by the rhythms and cadences of my alien mother’s other tongues” (9).

In her evocative words, her characters in MUH do not just use translation as a daily activity, but “realize that people who speak the same language are not necessarily the ones who understand each other best” (14). This was a language that was “slow-cooked” (23). As her characters like Dr Azad Bhartiya, Biplab Dasgupta (Garson Hobart), Tilo, and Musa begin to inhabit her mind and populate her fiction, boundaries between inside/outside, fiction/non-fiction become porous, permeable, and transparent. The Kashmiri-English alphabet becomes the final move towards creating a political idiom where the personal and the political integrally define each other, and are constitutively incomplete without each other. In a dramatic metaphor of reconstitution, she says, “I had to throw the language of TGOST off a very tall building. And then go down (using the stairs) to gather up the shattered pieces. So was born MUH” (32). Her answer to Neruda’s question – In What Language Does Rain Fall over Tormented Cities? – is “in the Language of Translation” (52).

Roy remains deeply suspicious of ‘causes’, and distances herself from titles like ‘activist.’ As she explains in an interview, this is because causes belong to everyone. Her engagement with various groups of people consciously remains an individual act that helps her to be constantly vigilant against attempts at appropriation by the establishment that may defang the critical impulse of her work. Humour in her writing allows flashes of rebellious and militant joy to erupt. Joy generates hope that adds yet another political dimension to her writing.

If writing can be a refuge and an expression of our collective rage, hope, and desire, it can also mark epistemological departures where multiple knowledges, languages, and ways of inhabiting the world intersect and interact. Roy’s writing opens for the reader critical vistas hitherto unexplored about the self and the world. With Roy, an unrelenting hope and rage are coupled with implacable courage born of the conviction that the job of the writer is to speak truth to power. In stubbornly refusing to be compartmentalised into externally imposed labels (like ‘fiction’ or ‘non-fiction’), her work exemplifies what it means to be human in the most profound ways possible. To ignore her is to ignore our humanity.

Primary Bibliography

Fiction:

Roy, Arundhati. The God of Small Things. Flamingo, 1997.

____. The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. Hamish Hamilton, 2017.

Non-Fiction:

Roy, Arundhati. The Cost of Living: The Greater Common Good and the End of Imagination. Flamingo, 1999.

____. Power Politics. South End Press, 2001.

____. The Algebra of Infinite Justice. Flamingo, 2002.

____. An Ordinary Person’s Guide to Empire. Consortium, 2004.

____. Listening to Grasshoppers: Field Notes on Democracy. Penguin, 2010.

____. Walking with the Comrades. Penguin, 2011.

____. Kashmir: The Case for Freedom. Verso, 2011.

____. Capitalism: A Ghost Story. Haymarket, 2014.

____. “The Doctor and the Saint”. Introduction to S. Anand (ed), Annotated edition of B R Ambedkar’s Annihilation of Caste. Navayana, 2015.

____. My Seditious Heart: Collected Non-Fiction. Haymarket. 2019.

____. Azadi: Freedom, Fascism, Fiction. Penguin, 2020.

Documentary

DAM/AGE: A Film with Arundhati Roy (2002). Last accessed 14 October 2022.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qlyZofTmUO4&ab_channel=theskeeboo

Interviews

“An Evening with 2022 St. Louis Literary Award Winner Arundhati Roy.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v-SVAFgEd5g (Last accessed 1 November 2022).

Aitkenhead, Decca. “‘Fiction takes its time’: Arundhati Roy on why it took 20 years to write her second novel.” The Guardian. 27 May 2017. Last accessed 17 October 2022.

Deb, Siddhartha. “Arundhati Roy, the Not-So-Reluctant Renegade.” The New York Times Magazine. 5 March 2014. Last accessed 3 October 2022.

Secondary Bibliography

Bose, Brinda. “In Desire and in Death: Eroticism as Politics in Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things.” ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature, vol. 29, no. 2, 1998, pp. 59-72.

____. ‘A fearless antinovel.’ Review of Arundhati Roy, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. Biblio: A Review of Books. July-September 2017.

Fuchs, Felix. “Novelizing Non-Fiction: Arundhati Roy’s Walking with the Comrades and the Critical Realism of Global Anglophone Literature.” Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies, vol. 23, no. 8, pp. 1187-1203, 2021.

Khair, Tabish. “India 2015: Magic, Modi, and Arundhati Roy.” The Journal of Commonwealth Literature, vol. 50, no. 3, 2015, pp. 398-406.

Menozzi, Filippo. “‘Too much blood for good literature’: Arundhati Roy’s The Ministry of Utmost Happiness and the question of realism.” Journal of Postcolonial Writing, vol. 55, no. 1, 2019, pp. 20-33.

____. “Beyond the Rhetoric of Belonging: Arundhati Roy and the Dalit Perspective.” Asiatic, vol. 10, no. 1, 2016, pp. 66-80.

Neumann, Birgit. “An ocean of languages? Multilingualism in Arundhati Roy’s The Ministry of Utmost Happiness.” The Journal of Commonwealth Literature. Published online: 29 April 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/00219894211007916

Prasad, Murari (editor). Arundhati Roy: Critical Perspectives. Pencraft, 2006.

Rajan, Romy. “Where Old Birds go to Die: Spaces of Precarity in Arundhati Roy’s The Ministry of Utmost Happiness.” ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature, vol. 52, no. 1, 2021, pp. 91-120.

Ramdev, Rina. “Arundhati Roy and the Framing of a ‘radicalised Dissent.’” Rule and Resistance Beyond the Nation State: Contestation, Escalation, Exit. Edited by Felix Anderl et al, pp. 243-256, Roman & Littlefield, 2019.

St. John, D. E. “Mobilizing the past: The God of Small Things’ automotive ecologies.” Journal of Postcolonial Writing, vol. 59, no. 1, 2023, pp. 1-14.

Subramanian, Samanth. “The Prescient Anger of Arundhati Roy.” Review of My Seditious Heart. The New Yorker. 12 June 2019.

Tickell, Alex. “Writing in the Necropolis: Arundhati Roy’s The Ministry of Utmost Happiness.” Moving Worlds: A Journal of Transcultural Studies, vol. 18, no. 1, 2018, pp. 100-112.

____. Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things. Routledge Guides to Literature. Routledge, 2007.

____. “The God of Small Things: Arundhati Roy’s Postcolonial Cosmopolitanism.” The Journal of Commonwealth Literature, vol. 38, no. 1, 2003, pp. 73-89.

Notes:

[1]https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/arundhati-roy-declines-sahitya-akademi-award/articleshow/1372130.cms The Times of India, 14 January 2006. Accessed 20 March 2023.

[2] https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/why-i-am-returning-my-award/ 5 Nov 2015. Accessed 20 March 2023.

[3] See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v-SVAFgEd5g, interview with Roy where she explains her different approaches to fiction and non-fiction. Accessed 1 Nov 2022.

[4] Rajmohan Gandhi, ‘Response to Arundhati Roy’. Economic and Political Weekly. 25 July 2015, vol. 50, no. 30, pp. 83-85.

[5] See the following to get a sense of the contours of this debate:

Bojja Tharakam, https://www.roundtableindia.co.in/without-arundhati-roy-without-anand-without-gandhi-the-book-had-its-own-value-bojja-tharakam/ 23 March 2014. Accessed 25 March 2023.

Shivam Vij, https://scroll.in/article/658279/why-dalit-radicals-dont-want-arundhati-roy-to-write-about-ambedkar. 12 March 2014. Accessed on 22 March 2023.

G Sampath, https://www.livemint.com/Opinion/dl8AvXg2PYchgE9qGogzJL/BR-Ambedkar-Arundhati-Roy-and-the-politics-of-appropriatio.html 19 March 2014. Accessed 22 March 2023