I.

Hospital

Illness rinses my insides

while I wait for you

to dye my hair.

Syringes and needles

lie carcass to a past

in my blood.

You like colour.

My paint is dark sputum,

sunlight a walking stick

with which you reward me.

We repeat passwords

of bank accounts.

Sweet lime, pomegranate,

apple, banana:

you fill my canvas

with demons of promises.

My tongue drains of its mother.

You scold me

in unfamiliar languages.

I sit straight in bed,

my spine in ballet.

“Good Health” is a skit

I now rehearse every evening.

The doctor claps

with stethoscope beats.

He borrows the sound

of my heart

for his orchestra.

You plan, like an ant

who’s suddenly discovered

this season’s immortality.

You hold my hand

as if it was an umbrella

you are opening into the rain.

You plug my ears

with your fingers:

the world is a firecracker

whose sound

you’re guarding me from.

But I can hear what they say.

I see it in their calendar faces.

You move wispy hair

from my forehead.

You count time in finger taps.

Convalescence arrives

like an unfulfilled expectation.

You treat health like bed linen,

ironing out its creases

around my body.

You teach me how to breathe,

to steal air from its march past.

You stir spoons in empty glasses,

you scold the thermometer,

you calculate, you wait

for my fever to dissolve

into inconsequential sweat.

You promise to take me home

as if I was a newly-wed bride.

You talk of the past

as if it was the future.

And when my body begins

making my future a past,

you look at me

as if I was an old photograph.

I wait for a new album.

II.

Tuberculosis

This disease makes of my life an untruth –

a long corridor of fasting.

Food and its epigrams of cure

accuse me of a career of neglect.

The rewards of weakness are few:

almost none, except a lover’s tourist care.

Every morning I am measured against myself.

I watch my shadows shrink into parenthesis.

Everything gets smaller – the dent on my pillow,

my signature on letters; and life.

Only my dreams stretch like elastic.

That, and the day. At night I am Keats,

sometimes Kafka, even Lawrence,

staring at death’s deep cleavage.

By day I’m a hospital poet.

But even my bones had strength once:

it carried the weight of your poems, you forget.

III.

Ulcer

The world’s mouthwash drains

into my gullet. The slap of acid

beat by beat, a fresco of corrosion

in the oesophagus. That beauty is

an untouchable the doctor spies on –

the betrayals of endoscopy.

*All great art comes from suffering.*

Now I know the pain of canvasses

as they are pinched by paint.

All sounds grow faint:

the crowd of pain is a roar

that drowns all other secrets.

I stay up to give it company.

I eavesdrop on hospital gossip

and watch the night fold into

an anthology of obituaries.

IV.

Surgery

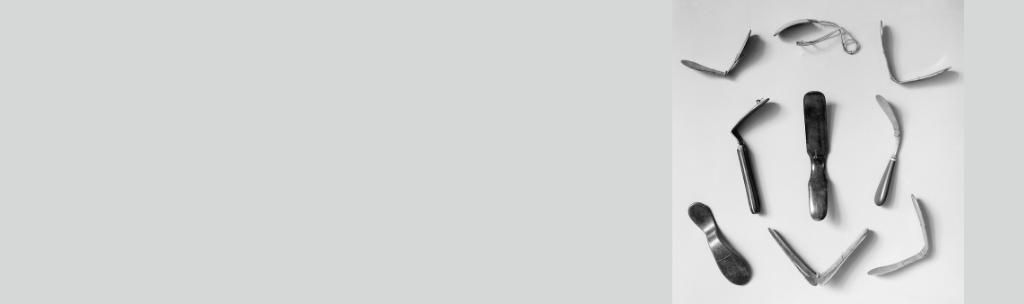

More knives have cut through me than men.

Insurance agents avoid me: I’m a ‘hospital whore’.

Needles no longer prick, they are an arsenal of nostalgia.

The chart in the nurse’s hand is a history textbook

doctors consult for reference. Vials annotate.

‘To’ and ‘OT’ form a palindrome around

which anaesthesiologists embalm my heartbeat.

Womanhood is an ambulance

screaming red light from a moving vehicle.

White. Distant. Only one mark of red.

It bleeds to no one’s command.

Nurses talk about aging as if it were a disease.

But men were once like trees, valued for age rings.

Nothing changes, almost nothing, the doctors say,

only a gradual slowing of the movement of oars

on a river I thought I’d tamed forever.

When I return home, restored but never quite the same,

I discover that death is always a hobo.

Now, all the news is on the neighbour’s TV,

all the aroma in yesterday’s leftovers.

Only the first night home after surgery

is what the day once was:

a reservoir of movement, the uterus a fledgling

insect trapped in marmalade on toast.